HEAL-funded researchers are testing phone-based physical therapy of basic stretches and strengthening exercises. Credit: Getty Images.

Low back pain is a significant driver of chronic pain and the leading cause of disability across the globe – many people either have it themselves or know someone who does. Although low back pain is very common and can come and go, it’s hard to live with. Most of the time, there is usually no single, fixable cause, which makes treatment difficult.

Low back pain affects people in all walks of life, but some are more prone: people with physically demanding jobs, those who are overweight or obese, and individuals with a low income. People with chronic low back pain are often prescribed opioids, even though research has shown that complementary or integrative health approaches that don’t involve medications work as well, if not better, and don’t carry risk of addiction. Examples are exercise, physical therapy, and spinal manipulation, as well as health coaching delivered by a trained counselor. Others include chiropractic care, yoga, and acupuncture – and various combinations of these approaches.

The trouble is that despite the proven effectiveness of complementary or integrative health approaches for low back pain, many people don’t use them. Fortunately, there is a whole area of healthcare research, called pragmatic clinical trials, devoted to solving public health challenges like this one. Pragmatic clinical trials test whether treatments already known to work under controlled settings can be effective in the “real world” (see Real-World Research). That means in everyday settings where people seek care and where various factors can affect whether a patient or a provider has access to a treatment and is willing to take it.

To help close the implementation gap for delivery of non-opioid treatments for low back pain, the Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®’s clinical research to improve pain management is funding several pragmatic clinical trials through the Pragmatic and Implementation Studies for the Management of Pain to Reduce Opioid Prescribing, or PRISM, program.

Real World Research

Often termed “real-world” research, pragmatic clinical trials were first introduced in the late 1960s but have gained traction in the last few decades. This research came to light because the results of many clinical trials to determine efficacy (“Does it work?”) can have limited impact on everyday practice (“Are people who could be helped actually using it?”). That’s because many clinical trials for efficacy are designed carefully to minimize variables: the hallmark of the scientific method.

For example, clinical trials testing whether a medication is safe and effective start with small numbers of carefully selected patient participants. Trials are then carried out by experienced investigators in specialized university hospital settings. Establishing these controlled environments help scientists tune out “noise” in the data they collect (for example, “Was the symptom caused by the test drug or another illness?”) that can obscure their ability to see if a drug works. These efficacy trials are the bedrock of safe and thorough clinical research.

But after knowing what works, as well as if it’s safe for use in people, the next step is implementation – putting treatments into practice in all types of environments where people seek care. That includes doctors’ offices, emergency rooms, and community health centers like the ones participating in Fritz’ study. This can be tough, and it’s where pragmatic research comes into play.

Pragmatic clinical trials enroll participants who are most likely to use a treatment – and they are conducted by the providers who will ultimately be delivering care in the communities where these people live. Pragmatic studies involve close collaboration with potential patient participants at all stages of the research. That includes helping researchers design recruitment materials, as well as define study outcomes that make sense to people’s lives: For example, instead of asking patients to grade pain on a scale of 1 to 10, they might ask if and how pain interferes with their life and work. Fritz’ study, for example, is using the Pain, Enjoyment of Life and General Activity (PEG) Scale to measure pain.

Another use of pragmatic research is to figure out how to combine effective treatments that have been proven to be safe and effective on their own, but not together. Fritz’ study, for example, blends two treatment approaches for back pain: cognitive behavioral therapy and physical therapy. Treatments that involve multiple components often require a team of different providers that center care around the needs of an individual patient. In this case, the research team involves physical therapists, experts in electronic health records, and psychologists.

Dual Challenges

Expanding use of complementary or integrative health approaches for low back pain means addressing dual challenges: first, increasing access to treatments, and second, raising awareness that they have been proven to work. The two problems are often related, and pain researcher and physical therapist Julie Fritz, Ph.D., P.T., of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City is addressing both in an NIH-funded pragmatic clinical trial involving people in Utah who receive care from federally qualified health centers (often called community health centers). These individuals often face many hurdles to staying healthy and getting state-of-the-art pain care because they live in very rural or low-income areas of the state.

“This research gives me an opportunity to think really creatively about bringing pain management solutions to low-income individuals who could benefit from them,” she says, “and it’s also a great way to involve individuals and communities often not included in research.”

As a pragmatic clinical trial, her study aims to overcome barriers specific to communities served by community health centers through innovative use of telehealth resources for managing pain. It will test how to implement two complementary or integrative health strategies for relieving back pain and reducing opioid use among patients in Utah community health centers. Both approaches will be offered remotely – a concept that’s increased in popularity and acceptance (including by government insurers like Medicare and Medicaid) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One strategy involves brief phone-based motivational support to help an individual manage her or his pain combined with phone-based physical therapy of basic stretches and strengthening exercises. The other strategy will test an adaptive, staged approach – providing the brief phone-based motivational support first, followed by the phone-based physical therapy program if the brief treatment is not successful. Both approaches are known to provide pain relief.

Fritz and her team are preparing to recruit participants and expect to begin the research in September 2021. They will measure pain and opioid use before and after the study period to see if the interventions have an effect on both among research participants compared to similar individuals not in the study.

Research for All People

Some parts of rural America are so remote that the federal government designates them as “frontier” land. Certain Utah counties, for example, have only a handful of residents over a thousand square miles. These places are so isolated that few doctors or nurse practitioners are available, and those that are around may not be aware of, or have access to, non-opioid pain options.

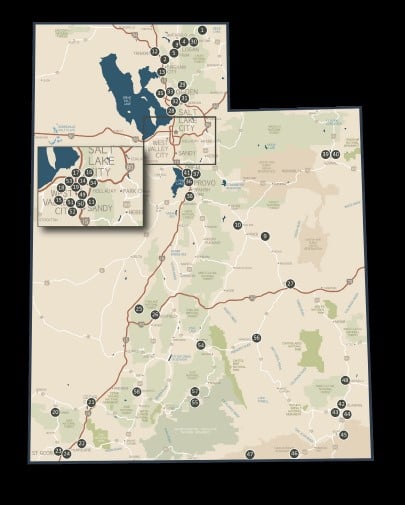

In Utah, 13 community health centers operate 54 clinics in rural areas like this but also in urban communities and in total provide care to about 20% of the state. Among Utah residents receiving care from community health centers, about half have no health insurance, and the vast majority, more than 90%, are low-income (at or below 200% of the federal poverty guidelines). In these cases, insurance coverage is a significant barrier to use of complementary or integrative health treatments for low back pain.

And although community health centers often serve communities at the forefront of the opioid crisis, they often lack options to provide accessible non-opioid pain care to the patients they serve.

Fritz’s study aims to figure out how to bring safe and effective back pain treatments to these individuals – with an eye to sharing successful strategies for use in other situations in which non-opioid treatments aren’t available.

Communication barriers and cultural acceptance also pose challenges for individuals receiving care in community health centers. Fritz estimates that about 30% to 40% of the target population for her study speak only Spanish, and so there is a need for bilingual providers who understand some of the unique needs of this community. Recruitment materials and communication strategies for the study are being tested in focus groups to be sure they are appropriate for the people she hopes to attract to participate in the study – and ultimately, to benefit from effective, low-cost pain management.

And because the treatment strategies Fritz is testing are delivered entirely over the phone – something most physical therapists have little experience with – part of training these providers involves teaching them psychology-based skills like motivational interviewing, which is used to tailor pain care to an individual’s unique needs and circumstances.

Fritz’ study involves people who receive care from Utah’s Community Health Centers, which provide care to individuals and families in urban and rural communities across the state regardless of ability to pay or insurance status.

Connecting the Dots

Another barrier that prevents uptake of research findings into communities is managing data – often an expensive and laborious process. Most pragmatic clinical trials involve several different “sites” where the research is done (in this case, about a dozen Utah community health centers) and they often take advantage of electronic health record systems that ease the ability to both track patient care and study results. Doing so saves money and time.

The urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic and its disproportionate effects on people from underrepresented minority groups prompted NIH to fund scientists to develop resources targeted to vulnerable groups. One such project in Utah, led by Fritz’ colleagues Rachel Hess, M.D., and David Wetter, Ph.D., is SCALE-UP Utah, a pragmatic research study conducted in 32 of the state’s community health clinics. It aims to increase the reach, uptake, and sustainability of COVID-19 screening and testing among underserved populations.

Because SCALE-UP Utah is using an electronic health record tracking tool already in use by Medicaid, it’s been a godsend for Fritz, who was fearing a “data nightmare” from loosely connected state- and county-level clinical settings. She has teamed up with Hess and Wetter to use the same tracking tool to collect data in her HEAL-funded work. Fritz also hopes to extract as much meaningful information as possible out of the electronic system – such as obtaining information about the economic and social conditions that influence individual and group differences in health outcomes.

“The real challenge is the transition from a project that’s funded by a grant to introducing its use in the real world – finding ways to support providers, physical therapists, and telehealth providers,” she explains, noting how important it is to engage patients, providers, and insurers from the get-go.

“We’re doing all of that as part of our research,” Fritz says. “And I always hope that if treatments are shown to be effective that we can all figure out how to get them to the people who need them.”

Find More Projects in This Research Focus Area

Explore programs and funded projects within the Clinical Strategies in Pain Management research focus area.

National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR)

Learn more about NINR’s role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services