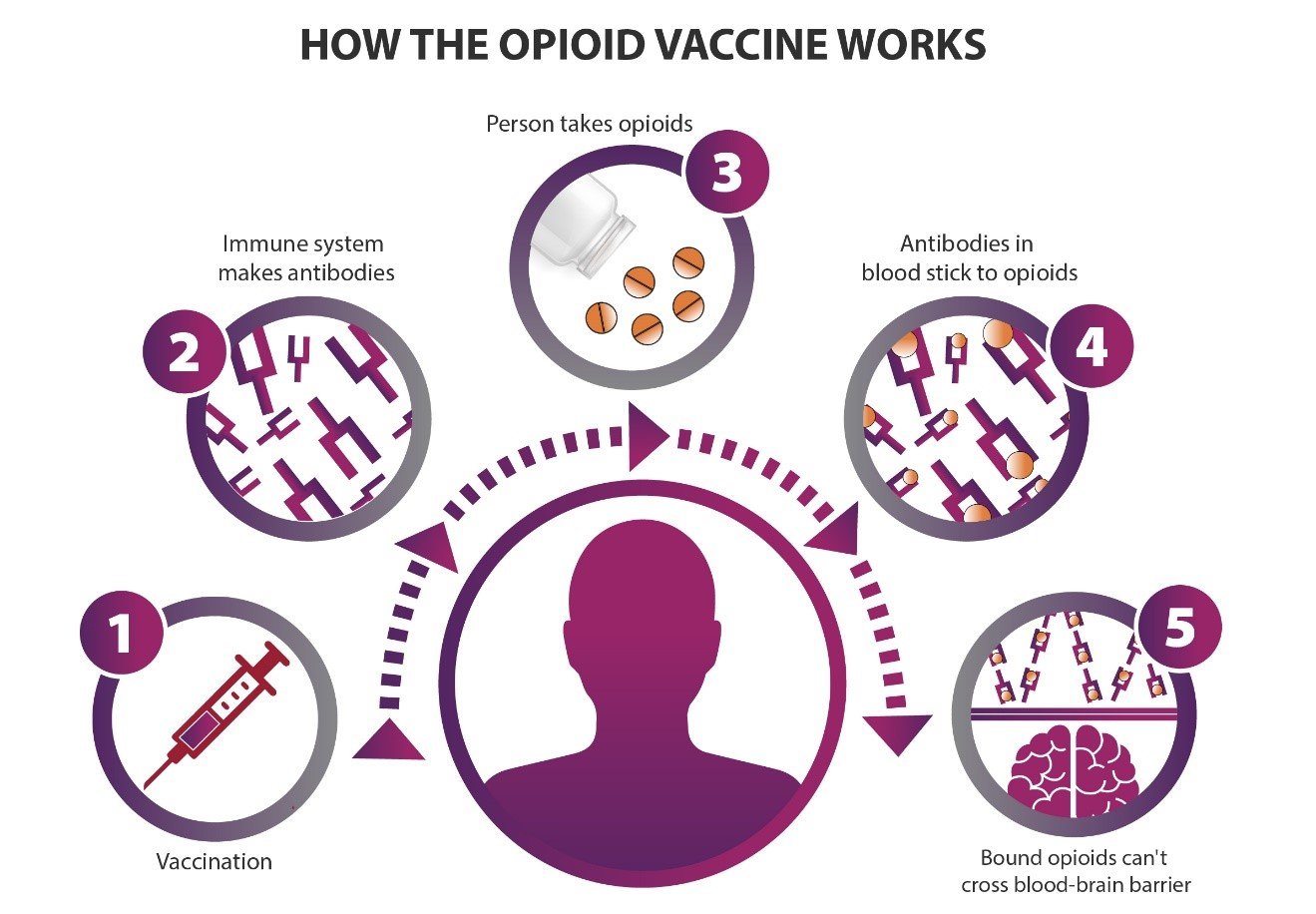

How an opioid vaccine works: (1) A person is vaccinated against one or more opioids. (2) The immune system makes antibodies to those opioids. (3) If a person takes opioids after vaccination, (4) the antibodies in the blood stick to the opioids, and (5) those opioids can’t cross from the blood into the brain. Credit: NIH HEAL Initiative

Vaccines remain one of the most important public health tools we have to fight disease. Preventive vaccines have led to the eradication of deadly diseases such as smallpox and are close to erasing polio from the world. The human papilloma virus vaccine prevents cervical cancer and is showing promise for some types of oral cancer.

But vaccines can also have potential beyond prevention: as treatments for people who already have a health condition. Researchers with the Helping to End Addiction Long-term® Initiative, or NIH HEAL Initiative®, are studying whether a vaccine can treat opioid use disorder.

There are three FDA-approved medications to treat opioid use disorder; however, more choices are needed to ensure that people have options that work for them and their individual needs. An opioid vaccine would be a new kind of treatment approach to provide protection against the effects of opioids, including overdose.

Preventing drug addiction

Researchers have been trying to make vaccines to treat drug addiction for a while. For example, people who received experimental vaccines against nicotine and cocaine made some antibodies that recognize these drugs, but not enough to cause a change in a person’s substance use.

Scientists have developed several experimental opioid vaccines and have shown that they are safe and effective in mice and rats. Marco Pravetoni, Ph.D., an immunologist and pharmacologist at the University of Minnesota, has shown, for example, that if a mouse is vaccinated against oxycodone, its immune cells start producing antibodies against oxycodone. When the animal is later given this particular opioid, the oxycodone-specific antibodies stick to it and prevent oxycodone from getting into the brain. The oxycodone can no longer produce a high or interfere with breathing — typically how an overdose becomes lethal.

Pravetoni and Sandra Comer, Ph.D., a neurobiologist and clinical researcher at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, are now starting the process of testing the first ever opioid vaccines in humans. The study is part of the NIH HEAL Initiative’s effort to find new medications for treating opioid use disorder and preventing overdose.

How it works

In general, vaccines work by teaching the body’s immune system to create antibodies that can recognize an antigen, a foreign substance or toxin like seasonal flu or tetanus. As with Pravetoni’s research with animal models, an opioid vaccine given to people would teach the body to make antibodies that recognize a target opioid. Later, when the target opioid molecules appear in the body, the antibodies stick to them and prevent the opioids from entering the brain.

But to get from blood to the brain, the opioid molecule (or any substance) must first pass through a physical barrier of cells called the blood-brain barrier. Normally, opioid molecules can get through because they are very small. But an opioid molecule that is stuck to an antibody would be too big to get through the barrier. The desired result: no pleasurable or rewarding effect, and no overdose death from decreased respiratory rate.

Opioid vaccines could be combined with other medications currently used to treat opioid use disorder, and they wouldn’t interfere with overdose rescue drugs like naloxone. Also, because vaccines produce antibodies that are highly specific to an opioid target, they would not interfere with the body’s natural abilities to control pain or with other pain management approaches.

Plans for human testing

Study researchers will first test an oxycodone vaccine in a small number of people with opioid use disorder and who are not seeking treatment. Each participant in the study will stay in an inpatient facility in New York or New Jersey for about two months. During that time, each person will receive multiple injections of oxycodone vaccine, spaced a few weeks apart.

The main goal of this first phase of vaccine testing is to monitor safety and see if participants develop antibodies against oxycodone. Researchers will also look for preliminary signs that the vaccine is blocking the effects of oxycodone. Before the first injection, each patient will have a test to find out what dose of oxycodone it takes for them to feel pleasurable effects. After each vaccination, the test will be repeated, to see if the vaccine makes the oxycodone less effective. A different opioid molecule will also be used to test the specificity of the vaccine response. If the vaccine works as expected, participants should have a less pleasurable response to oxycodone.

The researchers will also study how long the vaccine’s protection can last, estimating for now that the vaccine might protect against oxycodone effects for a few months. Longer-acting forms of treatment like a vaccine would theoretically help this type of treatment fit into people’s lives. And reducing the number of clinician visits can help people stay in treatment.

Through the NIH HEAL Initiative, Pravetoni is also leading development of a new fentanyl vaccine and collaborating with researchers at Virginia Tech to use the latest vaccine technologies. Another team is funded by the initiative to test a heroin vaccine in humans.

Like any vaccine, an opioid vaccine needs to be tested in many people before it could be made available more broadly. If it proves to be effective, a vaccine against opioids would be a valuable additional option for people with opioid use disorder.

Read About This Project on NIH RePORT

Learn more about Comer and Pravetoni’s project, “Phase 1A/1B clinical trials of multivalent opioid vaccine components."

Stay Connected

Stay up to date on the latest HEAL Initiative research advances by subscribing to receive HEAL content directly to your inbox.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

Learn more about NIDA’s role in the NIH HEAL Initiative.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services